It’s as American as baseball, mom and apple pie. Fresh, frozen, even canned, it has earned its standing as the preferred vegetable for most kids. And who among us can forget their dismay when Kevin Costner plowed a field of it to build, of all things, a baseball diamond?

It is, of course, corn; a seemingly innocuous entity that, thanks to technology developed by Cargill Dow LLC, today holds the promise of significantly and forever altering the market for thermoplastics—and helping to save the environment in the process. The goal, explains president Randy Howard, is to change the world by not changing it at all.

Cargill Dow LLC is banking on that fact that corn, a renewable and abundant resource, can replace the petrochemical-based plastics upon which so many fiber and packaging products are derived. It is so sure, in fact, that it is investing more than $300 million to bring to market the new NatureWorks™ polylactide (PLA) polymer.

What is a PLA polymer? And what exactly does it have to do with corn—or rather, billions of kernels of the popular yellow stuff?

Most people know polymers as man-made synthetics and fibers derived from petroleum: nylon and polyester are polymers, so is conventional plastic. The NatureWorks technology, on the other hand, harnesses the carbon naturally stored in plants to create a “natural” polymer that can be used for common consumer items such as clothing, cups, food containers and candy wrappers, as well as home and office furnishings. Because it uses annually renewable resources such as corn—and in the future, wheat, rice and beets—to create a natural polymer (polyactid acid or PLA), the NatureWorks PLA offers enormous environmental benefits; not only is it derived from a resource that is annually renewable, but the manufacturing process and the disposal ramifications provide significant environmental advantages as well.

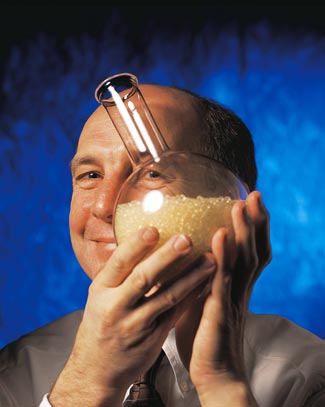

NatureWorks PLA is not an overnight sensation—yet. It has actually been more than a decade in the making. It began, innocently enough, with an assignment given to Dr. Pat Gruber, a newly-hired, fresh-out-of-school chemist at commodity grain processor Cargill Inc.: find new uses for corn sugars. That challenge lead to years of research and development in a quest for the best fermentation and distillation processes to create polymers derived from corn. Gruber admits to knocking on the doors of many a chemical company, only to be told that what he wanted to do just couldn’t be done. But he forged ahead, until one day, he recalls, the light bulb went off and he realized how the process could be accomplished. The next step was to build a small test plant; in 1994 he did just that, which began another learning curve: how to adjust the process to change the performance of the polymer for a variety of applications.

Enter Dow Chemical Co. In 1995, Dow recognized the significance of the work that had been initiated and began collaborating with Gruber and the team at Cargill to continue the R & D efforts. Working with employees on loan from both organizations, the NatureWorks technology flourished as it collaborated with outside plastic converters and fiber and fabric makers to develop test market applications.

In 1997, an official stand-alone company, Cargill Dow LLC, was formally “launched.” It operates today with 130 employees from headquarters in Minnetonka, MN, with a semi-works plant in Savage, MN, where it produces NatureWorks PLA in limited quantities for what it calls “marquee” customers—the companies with which it initially began working to develop end-products for consumers. (Most are market-development applications, although PLA-based clothing and packaging are already available in Japan.) A multi-million PLA polymer plant is currently under construction in Blair, NE. Expected to be fully operational by the end of 2001, annual production at the new plant is estimated to produce about 300 million pounds of PLA and use approximately 40,000 bushels of feed corn daily. Cargill Dow expects production to more than triple to one billion pounds before the end of this decade.

PLA is expected to use less about 20 to 50 percent less fossil resources than other thermoplastics. The company also predicts it will be able to further reduce energy requirements for its second and third manufacturing facilities, targeted for development as early as 2004.

Today, Cargill Dow LLC stands at a threshold to the future. It has huge hopes and dreams for the future, in large part because it recognizes that it is still in its infancy. “It’s important to realize that NatureWorks PLA is only 10 years old,” noted Gruber in a presentation at the Greenpeace Business conference in London, England, last October. “It has yet to begin to see the benefits of the 100 years of research of the chemical industry.”

Randy Howard, a former Dow Chemical Co. veteran, heads up the new joint venture as president. He recently spoke with green@work magazine about where the company has been, where it is today and, most importantly, where it is headed in the future.

How did Cargill and Dow come to work together on this project?

HOWARD: The technology to go from a renewable resource all the way to finished goods has been sought for many, many years. About 12 years ago, Dr. Pat Gruber and his colleagues made the development of this technology an all-time quest and continued it to the point that he found enough pieces of how to take the fermentation of technology from crops and turn that into chemicals that could then be taken further down the stream and polymerized into plastics. That brought him to the point of searching out a chemical company that could partner on this. That’s where the two parties came together. The company was formed in November of 1997 with a 10-year business plan created by the two parents. In January of this year, all of the employees who were on loan, and additional employees that we had hired, actually moved into the company of Cargill Dow. So effective January 1, we made another major move in being a stand-alone company. We operate the company from an executive committee and we have a board of directors or a members committee in which both Dow and Cargill have membership in, which approve our 10-year plan updates.

What was the impetus for pursuing this technology?

HOWARD: The whole background behind the drive to take fermentation chemistry forward into usable materials has always been the quest to turn renewable resources into finished goods that had equal or better performance than what’s available from petroleum-based products, which is really the competition as of today. That has been the main driving force that everyone has sought for a long time—until the technology developments came forward with Pat’s guidance in the last few years, it looked like a quest that was going to be very difficult to achieve. But with these recent advances, we’re well on our way at this point.

IS THERE AN ABUNDANCE OF CORN TO MEET YOUR NEEDS?

HOWARD: Well, if you look at it from the raw material standpoint, clearly we’ve targeted to take our first product line off of corn, or a product from corn actually—to take a sugar from corn and ferment that to lactic acid and on to NatureWorks PLA. If you look at our raw material source and you look at corn today, when we start up our plant in Blair, NE, in November of this year, that will take one stream from corn wet milling that runs at about 40,000 bushels per day. We’re only a component of that and that is only our first plant. When we get to capacity—as we look at the next 10 years—if we were to forecast out a billion-pound market, that’s less than half of one percent of the total U.S. corn crop that will be used to go into these plastics intermediate. So the abundance of raw materials is excellent for us at today’s farmland usage, which is about 75 percent of the usage in the U.S. So, all in all, the availability of raw material for us is very abundant and outstanding.

We also have a second generation that will complement this that actually takes the corn plant’s stocks and leaves, the by-products from the harvest, and not the grain itself. And we have technology that we’re putting into place that would be able to take those products into the same products that we make today. So we’ll be able to complement both the grain usage as well as a second source from the crops to achieve this.

How has the financial community—Wall Street—accepted this venture?

HOWARD: We’re not a publicly-traded company, so the Wall St. factor for us comes in a few different forms. We privately financed this venture even though we’re with two parents, and we were grossly over-subscribed by investors wanting to put money into the company. This is our first indication of what Wall St. believes in as to what our business plan is and where we’re going. The second part that we would consider to be analogous to Wall St. would be our customers—how they react and how they support us.

We have a small pilot plant with about 12 million pounds and that’s sold out for the rest of this year until the big plant comes on line. Our customers are very much in the product development mode. The supply rights agreements they’ve signed with us take material to the next increment of our capacity—which will be about 300 million pounds in November of this year.

Is the high level of customer interest a result of the product’s performance characteristics or its environmental benefits?

HOWARD: It’s an interesting mix. We’ve learned, clearly, that product performance is still number one. People buy products because they satisfy a need. We found that NatureWorks PLA has an overwhelming appeal to folks who not only are looking for performance properties in the sense of true performance, but also we are cost competitive with many of the fossil fuel-based raw materials and, on top of that, we come from a renewable resource. So really it’s the choice coming from the consumer’s standpoint looking at comparable or better performance and then having the accompanying attribute of coming from a renewable resource. The attention of the renewable resource factor has been absolutely outstanding.

Do you see a growing number of potential clients?

HOWARD: The company has targeted what we call “marquee” accounts. These are accounts that partnered with us in the beginning to have supply rights agreements with us. We are targeted very heavily on cooperating with them and helping build our NatureWorks brand image along with their brand image and putting those two things together to get started. After that, we’ll see where 300 million pounds leads to 600 million pounds leads to a billion pounds. But the reception at this point in time has been excellent.

Did you seek out these customers, or did they approach you?

HOWARD: It’s probably half and half. Since we launched the company publicly about a year ago, we’ve had a tremendous influx of inquiries. We also have been working with a lot of converters to convert products into downstream goods for consumers. So we have both things going—both the phone ringing with people interested in renewable resource products with excellent performance as well as companies we had partnered with in the beginning to get products out there and conduct market testing.

How is product development structured?

HOWARD: Currently the company is divided into three business units: one is packaging, one is fibers, and one is emerging or all-new types of activities. In the packaging area, films, food packaging, containers, rigid containers. In the fiber area, it’s for various fibers—for apparel, household, industrial, non-woven, filling and carpet applications.

What are some of the emerging activities?

HOWARD: We have more things aligned to technologies like injection blow molding for bottles. We have other chemicals and chemical intermediates that can be made from these materials. That’s more of a widespread application use. It’s a little bit of people having other ideas about what to do with the renewable resource-based polymer.

Can you make virtually any product that currently is made out of plastic or cloth out of NATUREWORKS PLA?

HOWARD: Every plastic has its inherent properties, and each plastic is better for certain applications, certain products. We fit very well into the middle range against other thermoplastics, but each one comes with its price differences, with its property differences. And then, clearly, we’re the only one that brings along renewable resources advantage.

Could soda bottles be made from this?

HOWARD: We have different types of polymers that come from this technology, different properties depending on how we process those and how we use the different products that we have. We can make most of these things. It still comes down to the issue of price and product performance. The other advantage that we have is in many of these segments we are compostable under certain conditions. So we do have a different benefit to offer people who are looking for certain types of renewable resource or recycling issues.

are all NATUREWORKS products biodegradable?

HOWARD: We use the term compostable; most of our work has been done with industrial compost units with the right temperature and the right humidity levels. And the answer to that is yes.

Are they recyclable?

HOWARD: Well, everyone has their definition of recycling, which can mean many different things. The uniqueness of this product is that it can be convertible back to its original monomer. Obviously, it takes infrastructure to collect and to reprocess, but that is the uniqueness of this being able to take it back to its monomer. We generally say it fits every waste stream including recycling back to monomer. And we are working on this approach with several accounts.

What has been the reaction of the farming community?

HOWARD: We had an excellent response from the National Corn Growers Association and they actually helped us with some of the technology developments, and they helped us with some of the lobbying for product development. It’s been an overall great response from associations relative to the farming community in addition to many of the states throughout the Midwest.

How did you choose Blair, NE, for the first plant site?

HOWARD: We have a need to be, obviously, close to corn milling operations where our raw material would come from. Cargill has a large corn milling operation in Blair—it was very easy for us to locate next to the site and to take one of the streams from the wet corn milling process. And I might add that we’ve had a great receptivity from the state of Nebraska in wanting to help us make this work in their state.

Are there any critics of the product?

HOWARD: The issue of criticism will, I believe, occur once there are more products out there; people want to see what you’re going to do with it, how it’s going to perform, where it’s going to go and how you’re going to handle the more delicate issues of recycling. Most of what you might call criticism has been along the lines of questions: How do you plan to handle this? How do you plan to handle that? So I would say comments have been more inquisitive than critical.

What are your biggest obstacles at present?

HOWARD: Well, obviously, the biggest thing on our mind right now is the very large leap we are taking. A lot of manufacturers go through steps in their processes where they can supply customers at intermediate sizes and quantities. We’re going from 12 million pounds to 300 million pounds in about nine months. So our concerns are a lot about coordination, partnerships with our downstream customers, making sure the plant starts up on time, delivery issues, etc. There’s a lot of focus on coordination at this point in time.

What has been the reaction from the traditional plastics industry TO NATUREWORKS?

HOWARD: It’s been a little bit of a ‘wait and see’ period. Many of the applications that we’re looking at are new and unique, contrary to generic substitution against other thermoplastics. We do know that there will be a product of choice based on best performance and best cost as well as the attributes that fit the product brand. So I would say that right now we plan on entering the plastics industry with something very new and very unique that has a lot of possibilities for recycling. We look at ourselves as joining that industry in the sense of the product we make versus attacking an individual, competitive product.

What are you most excited about at this point in time?

HOWARD: What’s great about being here is every day someone has a very unique idea about what the product can be used for, how it can be recycled, the best way to go about it. It is an innovative group like no other. The enthusiasm here and the pride of folks working on things that they really believe in is a uniqueness in the playing field. They are able to invent and innovate pretty much at will.

Do you want to build NatureWorks as a brand?

HOWARD: Yes, as well as partnering our brand with our customer’s brand—that could be a very powerful tool. From a consumer standpoint, obviously, getting to know NatureWorks as the product that it is and what it offers from the environmental standpoint is a real plus. So we clearly expect to continue to promote NatureWorks as a trade name and to take every advantage of that for ourselves and our customers.

Do consumers care about environmentally-friendly products?

HOWARD: I’m personally a very firm believer in that. I believe that education and awareness has come a long way in the past few years and that consumers are very interested and concerned about what they buy, where it comes from and how it’s taken care of after they’re done using it. I think that’s why we’ve had literally countless numbers of inquiries about what we’re doing and how we do it. And I believe that’s what plays to receiving awards from magazines such as Popular Mechanics and Industry Week—people are not only interested in the unique technology but are also looking to do the right thing.

Have you had any interest so far from the socially responsible investing front?

HOWARD: We have a lot of inquiries from different groups about how they can participate, and we’re evaluating all of those. At the present time, we have our hands full with the startup and the customers that we’re already committed to make successful. We do keep a very good running conversation with a lot of organizations about how they can help and how they can be involved.

How about NGOs—have you had active dialogues with them?

HOWARD: Very much so. As a matter of fact, Dr. Gruber just came back from the latest Greenpeace conference in London. Other groups have come to us to find out more about what we are doing.

You have been fairly quiet about this technology–there hasn’t been a lot of bell-ringing and fanfare. Is this intentional?

HOWARD: We actually have put a lot of effort and a lot of work into the launch which occurred about a year ago. What we’re managing right now is the very delicate issue of meeting commitments to customers based on a fairly small amount of material that we have available. And we’re managing expectations and managing product allocations to customers the best we can to get up to the 300-million-pound-a-year plan for November of this year. Clearly, we would have far more publicity and far more information in the marketplace if we had more product at this point in time, but we are clearly a startup company in the first 36 months of its operations. We are also a stand-alone company with a budget that needs to be managed, as I said, relative to a 10-year plan. So balancing all this and coordinating all of this is an absolute critical issue for us, particularly in the next 12 months.

What have you identified as the potential for this product within your 10-year plan?

HOWARD: We believe that we’re looking at at least a billion-pound NatureWorks PLA business forecast within that 10-year time frame. We announced publicly that Blair is our first plant operation and that we are planning plants two, three and four as we speak in locations yet to be determined based on feed stocks. So we do believe that is the size of this company, the size of that business in the foreseeable future. I would point out that with the tremendous innovativeness we see with our customers and our own folks on products and applications and use, this is a story yet to be told in completeness.

If the products in development for early customers are a huge success, there will be a lot of companies knocking at your door. What will happen when they do?

HOWARD: We think, for the most part, that the large market leaders in the segments with which we’re dealing will have such a great market reach with access to many different products and applications. Our intention is to stay closely tied to these market leaders and continue to work with them on product development as well as continuing to market our brand name along with theirs.

Could this technology ever replace traditional plastics?

HOWARD: No—all products have their own performance characteristics and work in certain types of environments better than others. This is not a replacement for the thermoplastics products that are in the marketplace today—in time or in total. I believe a polymer market today is in the 250 billion pound-plus range, growing at nine to 12 percent, in that kind of a ballpark. So we are a piece of the polymer market.

Do you expect your research to lead to new developments, new markets?

HOWARD: Absolutely. One of the hearts of the company is our ability to develop technology around the fermentation process. As technology continues to progress and folks here continue to look at other avenues, there are obviously other chemicals and other polymers that can be made by this process.

This product and process is obviously patented.

HOWARD: We have hundreds of patents in this area on product, processes and applications, and we are very well covered in the whole area of technology from

fermentation all the way forward to the polymerization itself.

How many employees does Cargill Dow have?

HOWARD: We’re a company of about a 130 people at the present time. We’ll reach and operate in the neighborhood of a 150 to 160 by the end of this year. Plant personnel will be in the 30 to 40 range and are excluded from those numbers. Future growth will obviously depend on where applications take us and the customers who continue to partner with us. We have roughly a 10 percent growth rate for 2002 planned at this time.

Are the current employees an equal mix from Cargill and Dow?

HOWARD: It’s probably about 40 percent from Cargill and 28 percent from Dow, and then quite a few people from the industry outside of either company. Actually, some people will argue that the Cargill employees were hired just for this effort so they’re really not Cargill employees.

What percentage of employees are involved in research?

HOWARD: Technical folks in our organization probably number 30 to 40 percent. They’re looking at all kinds of modifications of the polymer for different applications. We haven’t even touched on many of the things that you can do with this polymer relative to combining it with other things; one of the unique things in the polymer industry is that the combination of different polymers provides different properties. We have stayed pretty close to the PLA technology as it stands today, but there’s a whole other horizon out there of new products and new applications.

Do you consider yourself an entrepreneurial organization?

HOWARD: We are. One of the reasons to move to the stand-alone company approach is to give us the latitude to move in the direction that we need to on short notice. Our intent here is clearly to take every bit of advantage of that opportunity that both parents have given us. The executive committee does report to the board of directors or the members committee, which is represented by both parents. Also, we do play on the 10-year plan and our approach is to make that happen. Clearly, what comes with that are some fairly unique approaches that we’ve implemented and are driving us at a very fast pace.

What’s next?

HOWARD: We are extremely excited about the upcoming event in November. The new plant will create a very unique situation as we get product out there for the innovative companies that we work with to develop new products, new applications. We’ve coined a phrase around here, “There are no limits,” because there really are no limits to where we’re headed. We see nothing at this point in time that stands in the way of fulfilling all of what’s possible with this technology.

From green@work magazine – Cover story in the March/April 2001 Edition

(editor’s update 2011 – Cargill Dow LLC is now NatureWorks LLC)